Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier is still king of cool all these years later

MSG Network has replayed that Southern Illinois-Marquette NIT title game a few times in recent months and it’s pure gold, like getting a peek at Pacino’s screen test for “The Godfather” or Keith Richards working out an early version of the guitar riffs on “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.”

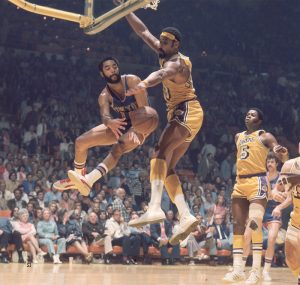

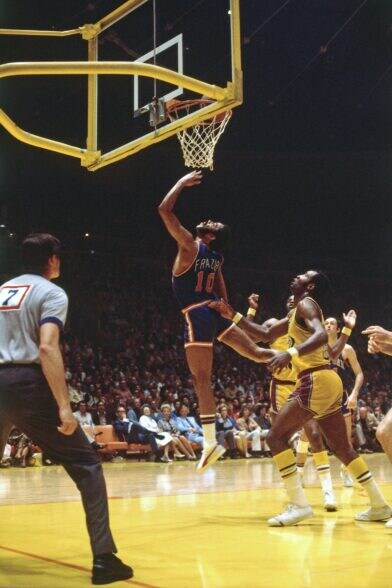

And you only need to have access to YouTube to see the greatest of all Frazier moments, the evening of May 8, 1970, Game 7 against the Lakers. Willis Reed captured the legend (and the MVP trophy) for hobbling onto the court and making his first two jumpers, the only baskets he scored. The rest of the night — and the rest of Knicks eternity — belonged to Frazier — who had 36 points and 19 assists and seven rebounds and looks, on that grainy tape, like one of the greatest players of all time.

Which he most certainly was.

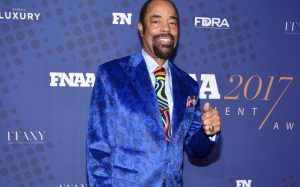

But there is more, so much more to Frazier than what he did on the court. At a time when we laud athletes who don’t sneer in public, Frazier is in his seventh decade in putting smiles on the faces of everyone he comes in contact with. That includes campers who learned from him in the ’60s, fans who he thrilled in the ’70s, listeners who tuned into the radio in the ’80s, viewers who became next-generation fans in the ’90s, and so many who weren’t born yet on May 8, 1970, who have heard his rhymes and seen his glorious wardrobe in the aughts and the ’10s and now the ’20s.

“I like people,” he once told me, and all you need to do is see him interact with people — all kinds, all classes, all colors, all creeds — and you understand. It was George Kalinsky — equally gifted behind his camera as Frazier was on the court — who gave birth to “Clyde,” a pantheon New York nickname (alongside, if not a smidge higher, than “Broadway Joe” and “Babe”) by taking a series of iconic pictures early in his career.

And Clyde he has remained, an icon of greatness as an athlete and of goodness as a man. A friend recalled recently seeing Clyde rushing to work one day in the morass of Penn Station and my buddy said, “Hey, Clyde, give us a rhyme!”

“Haven’t got the time!” he said, smiling and buzzing past, giving him the rhyme even in a hurry, still figuring away to please and give a story he’ll tell the rest of his life.

One of the first sports books I read as a kid was a glorious title called “Rockin’ Steady: A Guide to Basketball & Cool,” which Clyde co-authored in 1974 with Ira Berkow (who himself knows a thing or two about “cool” since he was still running full-court pickup games alongside the likes of Oscar Robertson as he approached 70).

There were some useful basketball thoughts from Clyde on dunking (he thought it a needless risk; just “lay it in easy,” he advised) and passing (“I’ve seen guys make fancy passes that wow the crowd and bounce off the back of a teammate’s head; that’s not playmaking”) and defense (“Never cross your feet!”) and shooting (“I shoot on a line drive when I’m alone, with an arc when there’s some cat climbing my chest”).

But the essential advice was on the other side of the ampersand, covered in chapters subtitled “Cool” and “A General Guide to Looking Good, and Other Matters.” When I was 7, I was desperate to be cool and Clyde showed me how, for everything from showers (“I take a lukewarm shower, then a cold shower. Stimulates the blood.”) to toweling off (“Use short, brisk movements”) to the part everyone who’s read the book remembers: how to properly (and stylishly) catch a fly.

Wrong: Hover over fly, slam hand (illustrated).

Right: Approach fly from the side, relax and “bring flexor muscles to a spring-like tension.”

I read it again this week (it’s still in print; get it). He was cool then. He’s cool still. He is a treasure (and, as he would surely add, a pleasure).

Walt Frazier

|

Frazier in March 2020

|

|

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | March 29, 1945 Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Listed height | 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) |

| Listed weight | 200 lb (91 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | David T. Howard (Atlanta, Georgia) |

| College | Southern Illinois (1963–1967) |

| NBA draft | 1967 / Round: 1 / Pick: 5th overall |

| Selected by the New York Knicks | |

| Playing career | 1967–1979 |

| Position | Point guard |

| Number | 10, 11 |

| Career history | |

| 1967–1977 | New York Knicks |

| 1977–1979 | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| Career highlights and awards | |

|

|

| Career statistics | |

| Points | 15,581 (18.9 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 4,830 (5.9 rpg) |

| Assists | 5,040 (6.1 apg) |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 |

|

Walter “Clyde” Frazier Jr. (born March 29, 1945) is an American former professional basketball player of the National Basketball Association (NBA). As their floor general and top perimeter defender, he led the New York Knicks to the franchise’s only two championships (1970 and 1973), and was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1987. Upon his retirement from basketball, Frazier went into broadcasting; he is currently a color commentator for telecasts of Knicks games on the MSG Network.

Legends profile: Walt Frazier

He started slowly, averaging only 9.0 points in 1967-68. “My rookie year, I really played lousy at first,” he recalled in Sport. But midway through that season a new coach, William “Red” Holzman, took charge of the Knicks and emphasized the aggressive defense that was Frazier’s strongest suit. The rookie’s playing time soared, as did his confidence. Frazier and teammate Phil Jackson, who would later gain more fame as the head coach two dynasties: the Chicago Bulls and the Los Angeles Lakers, were named to the NBA All-Rookie Team at season’s end.

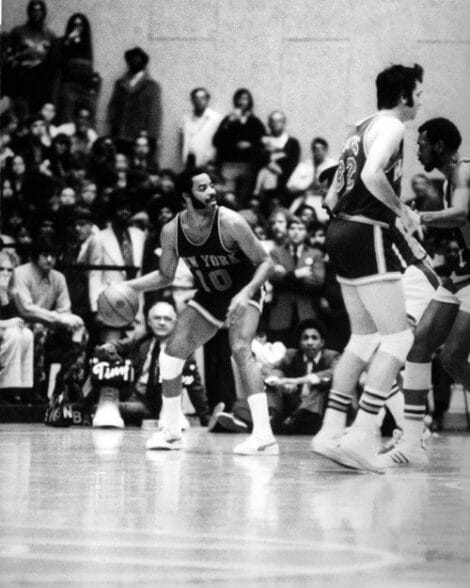

Possessing exceptional peripheral vision and quick hands — “faster than a lizard’s tongue,” commented one opponent –Frazier began delighting New York fans with sudden steals and lightning passes. “The great thing about Clyde are his hands, his anticipation,” Holzman told Sport. Added teammate Bill Bradley, “[Frazier] is the only player I’ve ever seen [whom] I would describe as an artist, who takes an artistic approach to the game.”

By adding Frazier, Bradley, and Dave DeBusschere to a starting lineup that already featured center Willis Reed and guard Dick Barnett, the Knicks quickly built an unusually well-balanced club, a championship contender that reached the Eastern Division Finals in 1968-69. Frazier averaged 17.5 points that season and earned the first of seven consecutive selections to the NBA All-Defensive First Team.

Early in the 1969-70 season, the Knicks won 18 consecutive games, setting a new NBA record, and went on to a league-best 60-22 mark in the regular season. The team’s unprecedented emphasis on defense, led by Frazier, showed in two remarkable statistics: the Knicks achieved the best record in the NBA with their leading scorer, Reed, ranking only 15th in the league; and their defense allowed just 105.9 points per game, nearly 6 points better than their closest rival. Frazier averaged 20.9 points and 8.2 assists for the season. He made the first of seven successive All-Star appearances and earned the first of four selections to the All-NBA First Team.

The 1970 NBA Finals matched two superlative clubs, the Knicks and the Los Angeles Lakers, representing the country’s two biggest metropolitan centers. The seven-game series generated more national excitement than the NBA had ever known. Pitted against a Lakers club that featured such legends as Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry West and Elgin Baylor, the Knicks battled their rivals to a deadlock through six games, despite a leg injury to Reed, their top scorer, in Game 5.

In the decisive seventh game at Madison Square Garden, Reed hobbled dramatically onto the court, long enough to score the first two baskets of the game. Then he turned the spotlight over to Frazier, who responded with one of the greatest performances ever in a Finals Game 7: 36 points, 19 assists and five steals — including a

A certified hero in New York, Frazier became as well known for his stylish attire and after-hours partying as for his ballhandling and peerless defense. This led to many magazine articles, photoshoots as well as commercial advertising opportunities. He parlayed his cool persona into becoming one of the first athletes to be paid to wear a basketball sneaker — a suede version made by Puma.

On the court, he led the Knicks to four more winning seasons. In 1971 New York reached the Eastern Conference Finals but lost to the Baltimore Bullets in seven games. The Knicks returned to the NBA Finals in 1972 but fell to a powerful Lakers team that had gone 69-13 in the regular season.

Early in the 1971-72 season the Knicks acquired guard Earl Monroe, an archnemesis of Frazier’s, from Baltimore. Skeptics said the longtime rivals were a disastrous match, but instead the storied “Rolls-Royce backcourt” gave the Knicks an even more formidable defense. “He’s fire and I’m ice,” Frazier said of Monroe in Newsday. In 1972-73, the pair’s first full season together, New York defeated the Boston Celtics in the Eastern Conference Finals and then regained the championship by downing the Lakers in five games.

His second championship ring marked the peak of Frazier’s career. The Knicks began a steady decline that saw them fall out of championship form and then out of the playoffs entirely by 1976. Frazier, meanwhile, turned in three more All-Star seasons and even captured the All-Star Game MVP Award after a 30-point performance in 1975. In 1976-77, his scoring average dipped to 17.4 points per game, and the Knicks missed the playoffs for the second straight year.

On the eve of the 1977-78 season New York sent Frazier to the Cleveland Cavaliers as compensation for the free-agent signing of Jim Cleamons. With that move one of the most glorious careers in Knicks history came to an end. At the time, Frazier ranked as the Knicks’ all-time leader in scoring (14,617 points), assists (4,791), games played (759) and minutes (28,995). Patrick Ewing would eventually surpass him in all those categories except assists.

Frazier was stunned by the trade but dutifully reported to Cleveland after a decade in the Manhattan limelight. The move did not, however, restore the on-court skills of his prime. Partly hampered by repeated foot injuries, Frazier played in only 66 games over portions of three seasons in Cleveland before the Cavaliers put him on waivers three games into the 1979-80 campaign.

In retirement Frazier set up shop as a player agent, invested in a franchise in the short-lived United States Basketball League and then moved to the U.S. Virgin Islands and obtained a charter-boat captain’s license. But he lost both a home and a boat to Hurricane Hugo, and in 1989 he moved back to New York to work as an analyst on Knicks broadcasts. In that role, the ever-colorful Frazier delighted and confounded New York fans with a constant barrage of rhyming phrases and creative word usage — “Clyde-isms,” as they came to be known.

When his playing days had concluded, Frazier’s accomplishments on the court were still being acknowledged. In 1979, the Knicks retired Frazier’s No. 10 jersey. In 1987, he was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. And in 1996, he was elected to the NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team.

Style

Since the late 1960s, Frazier has been known for being a fashion icon and was one of the first major pro athletes to be acclaimed as such. The website Clyde So Fly catalogs and grades every suit he wears while broadcasting New York Knicks games on the MSG Network.

Frazier also has a line of Puma sneakers named after him. The promotional material references Frazier’s “signature colorful style”.

Personal life

Frazier lives in Harlem with his long-term girlfriend, Patricia James, and they also have a home in St. Croix. He is the father of a son referred to both as Walt Jr. and, later, Walt III. Frazier is a member of the fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha.